Credit

2017 Jean Delville/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, via SABAM, Brussels; Royal Museums of Fine Arts, Belgium, Brussels

Let’s say you were a composer, and you wrote a symphony that received universal praise, deep academic study, performances by the most prestigious orchestras. Critics called you an heir to Bach and Beethoven. But you had a secret: Before you were famous, the music that spoke to you most was “MacArthur Park,” “I Would Do Anything for Love” and other bombastic tunes of passion and loss. You outgrew it, sure. But between the notes, in the deep recesses of your symphony, that early taste for trash was still there.

Something like that happened with European modern art — and it’s a tale historians have often resisted telling. The development of abstraction at the start of the last century is often told as a steady, formal progression, but many pre-World War I artists were not thinking only about color and line. They were infatuated, too, with unhinged emotion and mystical mumbo-jumbo, and the art that inspired that generation was, often, spiritualist schlock.

Credit

Philip Greenberg for The New York Times

It’s on view in the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s revelatory and brilliantly tasteless “Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rose+Croix in Paris, 1892-1897,” which plunges viewers into a Symbolist painting salon that shocked and enraptured viewers in the last decade of the 19th century. While Cézanne and van Gogh were down in Provence analyzing mountains and apples, up in Paris artists allied with a strange writer/spiritualist/charlatan named Joséphin Péladan turned away from observation and toward over-the-top religious fantasy. All the paintings in this Guggenheim show were displayed in Péladan’s annual, highly publicized exhibition: plaintive Orpheuses; pale femmes fatales; virginal maids in the wilderness, their pallid skin rendered in soft, vaporous brush strokes.

All of them are excessive. Many are simply gross. But they are weirdly compelling, and for a host of later modernists — writers like Pound and Yeats, artists like Mondrian and Kandinsky — this sort of garbage spiritualism came like a breath of life after the rigors of realism. Hung at the Guggenheim against deep carmine walls, and with Wagner’s “Parsifal” overture occasionally blasting from speakers overhead, “Mystical Symbolism” goes all in on the decadence of the Salon de la Rose+Croix. (It has been organized by Vivien Greene, a Guggenheim curator, who also edited an illuminating catalog.)

Credit

Philip Greenberg for The New York Times

Péladan (1859-1918) was an author, critic and leader of a secret society, the Ordre de la Rose+Croix du Temple et du Graal, that was one of several occult sects to arise during the Belle Époque. He was also an avowed monarchist in republican France, and bestowed upon himself the bogus honorific of Sar: “leader” in Assyrian. Two portraits of him here give a sense of his showmanship. One, from 1891, pictures him with a fur hat and a dandyish lace collar; by 1895, his colleague Jean Delville painted him as a saint in white robes, eyes locked on the heavens, his finger extended forth as if preparing to bestow a revelation.

Was Péladan serious? Parisians in the 1890s couldn’t tell — a case of clippings here includes mocking reports from newspapers of the day — but he certainly acted the part, and the artists he invited to exhibit in the Rose+Croix salons had to obey strict precepts: no still lifes, no landscapes, only art in the service of the divine. Often that took a Catholic turn, as in the divisionist “Vision,” by Alphonse Osbert, in which a shepherdess gazes upward while a halo springs from her head and a lamb nuzzles her leg. But Péladan’s spirituality was omnivorous, and other paintings here invoke Greco-Roman motifs, especially the myth of Orpheus, and esoteric rites. The Rose+Croix artists’ other deity was Wagner, whose long operas, especially the late “Parsifal,” treated art itself as a religious practice. Etchings after that opera by the Spanish artist Rogelio de Egusquiza, who met Péladan at Wagner’s custom-built theater in Bayreuth, appeared in the 1896 edition of the salon. The Guggenheim is exhibiting his gassy rendering of the holy grail, radiating light while a dove spreads its beneficent wings.

Credit

2017 Jean Delville/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Philip Greenberg for The New York Times

These artists shared the spiritual inclinations of the Symbolists before them, among them Gustave Moreau and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. They also dovetail with the Pre-Raphaelites across the English Channel, who had similar tastes for knights’ chalices and longhaired maidens. But there’s a profligacy and messiness to much of the Salon de la Rose+Croix that makes it stand apart from those more refined predecessors. Photographs can do only so much to convey how overwrought some of these paintings are — and how they can beguile as much as they nauseate.

Continue reading the main story

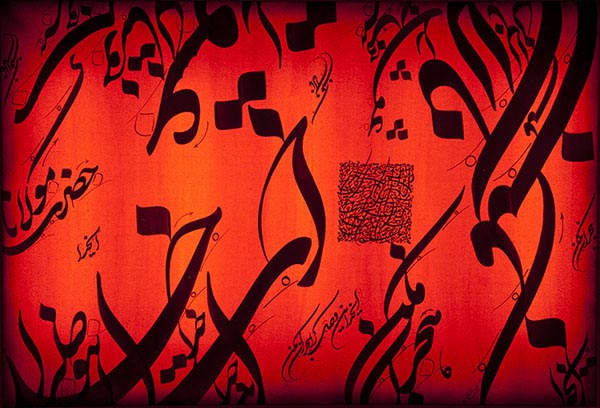

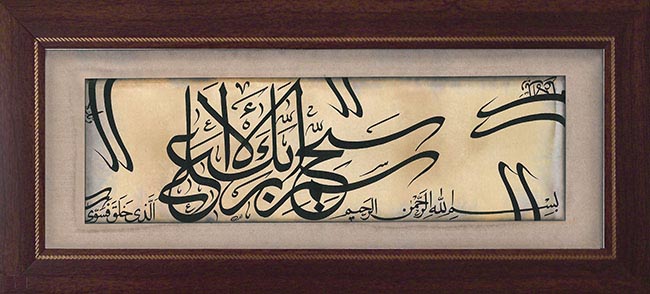

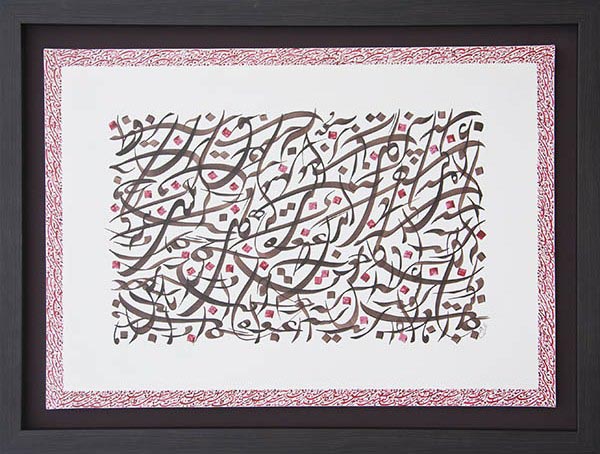

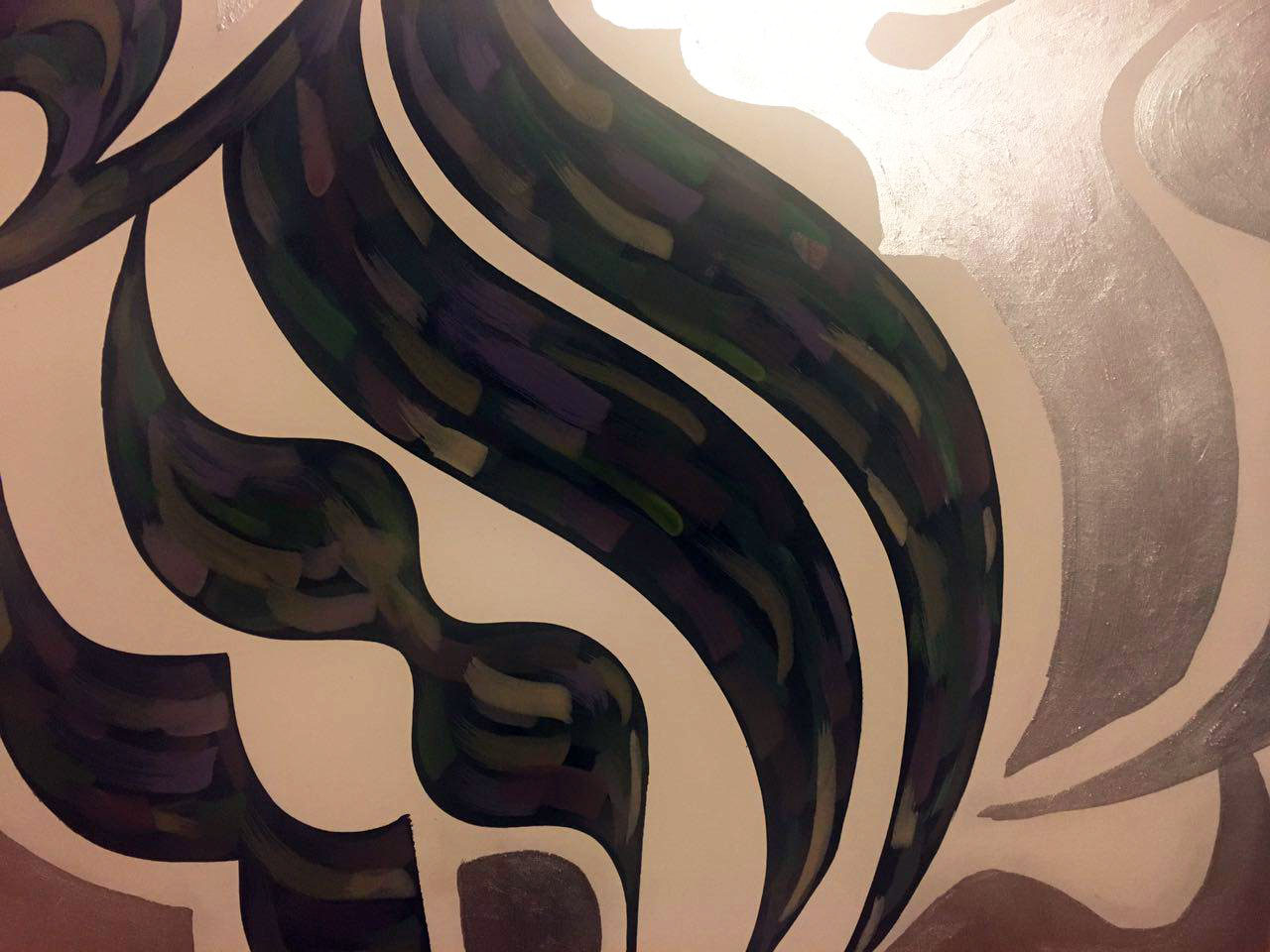

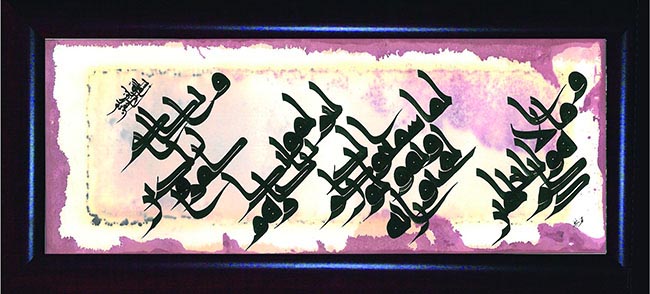

Ebrahim olfat | Calligraphy | Modern Calligraphy | 09121958036 | ebrahimolfat.com