The hourlong train ride from New York City to Morris County, N.J., cuts through the dreary industrial swamp of the Meadowlands, goes past the concrete caverns of Newark and edges along leafy college towns, before finally ending in Morristown, the county seat, a Revolutionary War stronghold and the former site of the curiously named Fort Nonsense, now a nondescript village full of hulking suburban houses. (In an episode of the final season of ‘‘The Sopranos,’’ Morristown is where Tony Soprano dreams he goes to die, just before waking from a gunshot-induced coma.) A 30-minute drive from Morristown is Chester, a tiny, bucolic community of horse farms, where families of deer amble down narrow roads and rolling hills loom hazily in the distant skyline. There, at the end of a dirt path, is a sight so unexpected that it feels as if it had descended from another world, quietly and without explanation: the country home of the artist Cai Guo-Qiang, designed by his friend Frank Gehry.

Cai is best known for what he calls ‘‘outdoor explosion events,’’ public installations in which the medium is gunpowder, his signature material. Gehry shoulders the burdensome mantle of being the World’s Most Famous Architect: The phrase ‘‘Bilbao effect’’ — which was coined after he designed an outpost of the Guggenheim Museum in what had been a depressed postindustrial Spanish town — has entered popular usage as a means of explaining how the presence of a marquee architect’s buildings, and Gehry’s in particular, can transform a city’s fortunes.

Chester, which Cai stumbled upon while looking specifically for ‘‘a huge horse barn where I could create artworks,’’ is unlikely to become a global destination. But his home here does answer the question of how one popular artist creates a place to work and live for another. Contemporary art and architecture are often thought of as contiguous, at least since the postwar era, when the division between various practices — sculpture, painting, design — began to collapse. Gehry’s swoopy, postmodernist buildings have often been compared to the work of like-minded artists, including Claes Oldenburg — Gehry designed the Chiat/Day Building in L.A. around Oldenburg’s 1991 ‘‘Giant Binoculars’’ sculpture — and Richard Serra, who once noted, ‘‘Frank and I have been talking to each other through our work for years.’’ Still, it’s rare for a living architect to be considered an actual artist, and artists generally avoid creating habitable structures. Gehry is unusual in his ability to straddle both worlds — he’s had exhibitions of his designs at galleries and museums, and he’s described his buildings as having ‘‘movement and feeling.’’ He’s also built homes for artists in the past, most famously Ron Davis, though many of those projects, he told me, were anonymous. (‘‘It was the L.A. art scene,’’ he said, ‘‘and it was just friends and we would help each other.’’)

Credit

Stefan Ruiz

Credit

Stefan Ruiz

Credit

Stefan Ruiz

Credit

Stefan Ruiz

If Oldenburg’s sculptures of repurposed household objects were an aesthetic precursor to Gehry’s designs, which often make use of ordinary materials, Cai and Gehry have much less in common aesthetically beyond a shared interest in theatricality. That an architect and an artist as different as Cai and Gehry have had any ongoing creative dialogue at all is remarkable; that the most complete expression of that dialogue is a weekend home hidden in the New Jersey countryside is even more so. And yet Gehry’s house for Cai, designed in collaboration with his former student Trattie Davies, is a kind of brick and mortar reflection of Cai’s character: by turns boisterous and understated, flamboyant but ultimately serene.

Studio Visit | Cai Guo-Qiang

A day with the artist at his Frank Gehry-designed country compound.

By JASON SCHMIDT on Publish Date August 19, 2017.

.

Watch in Times Video »

One morning in early June, Cai greeted me in Chester. He had the haircut of a drill sergeant, which belied his occasional bursts of giddiness. He bought the former horse farm, built in the 1920s, from an Olympian equestrian in 2011. (The horse is New Jersey’s official state animal, and the headquarters of the U.S. Equestrian Team is in nearby Gladstone.) The barn where the previous owner used to train is now a 14,000-square-foot studio, large enough to drive a truck directly inside and unload materials. (Many of Cai’s paintings require controlled explosions of gunpowder and pigment, and for the last several years, he’s made these at a fireworks factory on Long Island; new works in this series will debut at an exhibition at the Prado Museum in Madrid this fall.) The stables — which for now look as if they’ve only recently been abandoned by horses — will become archives and, once the hayloft is removed, give way to an exhibition space with towering ceilings for large-scale pieces.

Cai has had many elaborate studios — including his current one in Manhattan, renovated by Rem Koolhaas’s OMA firm — but they’ve all been separate from his home life. He eventually plans to turn this property into a foundation open to the public, but for now, he can both work and spend time with his wife and two daughters. Combining his personal life with his professional one, he said, was one of his goals. ‘‘An artist is like a cook,’’ Cai told me, his studio manager translating his Mandarin to English, ‘‘who needs not only the dining area but also the kitchen.’’

Credit

Stefan Ruiz

Credit

Stefan Ruiz

Credit

Stefan Ruiz

Credit

Stefan Ruiz

The 9,700-square-foot main house is a cluster of glass-and-sequoia structures with titanium rooftops that seem to curl up at the ends, which Gehry designed to look like flying carpets. The facade is embellished with numerous small balconies that jut out of corners, adding a complex geometry to the original stone core. Artists, Gehry told me by phone, are ‘‘willing to explore visual thinking. Most people don’t think that way.’’ He’s working on another house now, for a technology entrepreneur, and, he told me, she thinks more like a building contractor. ‘‘We supply the art and she gets it built,’’ he said. ‘‘So it’s a different attitude, and I love that — that different clients come with a different point of view. If you can tap into that as an architect, that’s great, because the building gets personalized. The flying carpets are about Cai. I think they resonate with him.’’ (Cai broke into laughter when I asked him if flying carpet rooftops were something he requested from Gehry. ‘‘If I said, ‘Oh, Frank, can we do flying carpets?’ he would say, ‘Design it yourself.’ ’’ Asked about Cai’s specifications, Gehry said, ‘‘Well, he talked about how he needed a bedroom.’’)

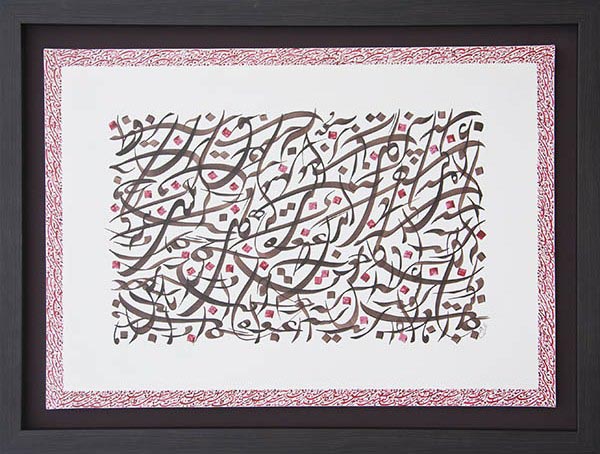

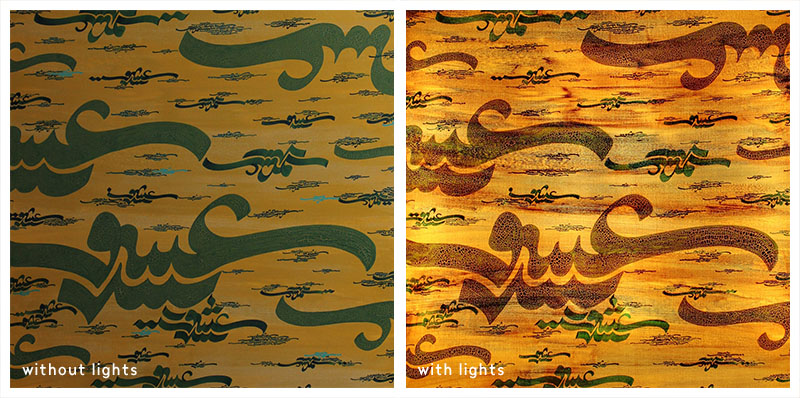

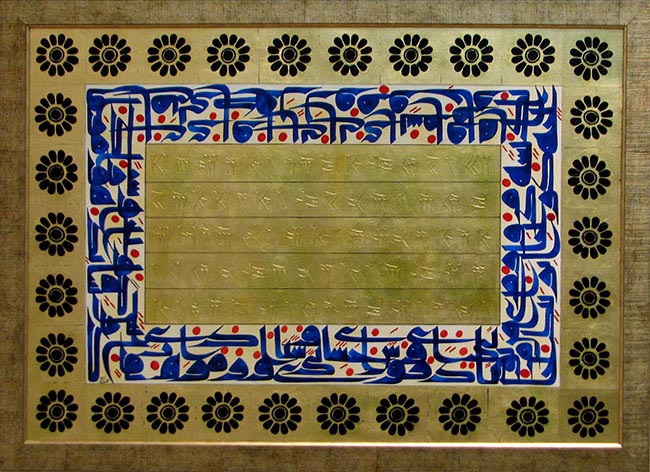

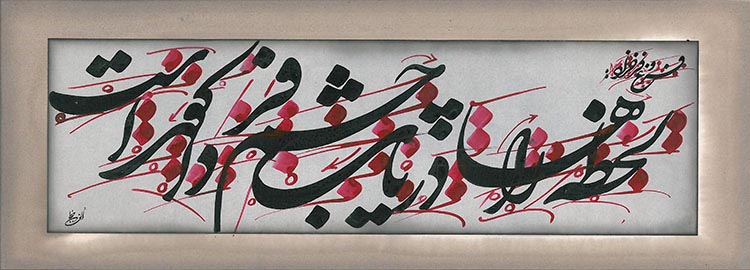

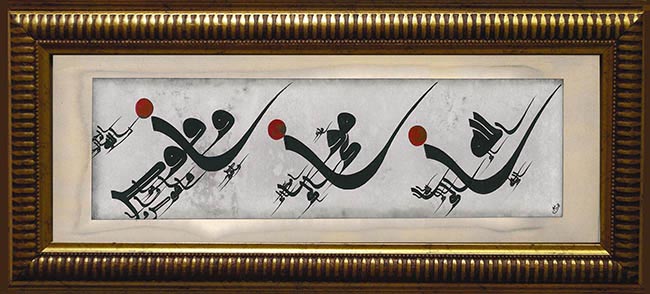

Ebrahim olfat | Calligraphy | Modern Calligraphy | 09121958036 | ebrahimolfat.com