But now, at 75, with mental health issues and old physical injuries that have forced a retreat from hands-on work, Mr. Chihuly is facing a hard-edge court battle — and a potential cloud over his life and art — around the question of what those teams do. A former contractor has sued him and his wife, Leslie, who is the president and chief executive of Chihuly Studio, seeking compensation for millions of dollars of paintings that the contractor says he created or inspired, but for which he said he was never properly credited or compensated.

Credit

Kyle Johnson for The New York Times

These are painful days for Dale Chihuly, as he winds down a long career facing a challenge that stabs at the heart of any artist: his originality. Mr. Chihuly emblazoned his signature on the world by working and rethinking the vocabulary of glass as art. Physical challenges and scars compounded the difficulty of that path. He lost vision in an eye in a 1976 car crash that also permanently injured an ankle and a foot. A shoulder injury from a bodysurfing accident made glass blowing, with its heavy weights of pipes and glass, impossible to do. He suffers from bipolar disorder, marked by sweeping swings of elation and depression. And with greater dependence on others, he said, has come greater vulnerability to claims that his work is not his own.

Credit

Kyle Johnson for The New York Times

“Yeah, I would say it probably made it easier to attack me,” he said. “I absolutely need my teams.”

The Chihulys, in their own countersuit in Federal District Court in Seattle, have dismissed the claim by the former vendor, Michael Moi, as an act of greed and jealousy. They said that Mr. Chihuly’s vision still defines and shapes all art that leaves his studio.

“He was a handyman,” Ms. Chihuly said of Mr. Moi’s role in the company, which employs about 100 people in several locations in the Seattle area.

Mr. Moi’s lawsuit says that exploitation and uncredited work were built into the Chihuly team system, and that the mental swings of working under a bipolar artist — manic bouts of energy followed by crashes of depression and paranoia — were part of the unpredictable dynamic of how and when work got done, and who did it. Mr. Moi, through his lawyer, declined a request for an interview.

“Up-and-down manic cycles were a constant,” the suit says.

Certainly, workshops for art, overseen by an artist with a famous name, are nothing new. Painters from Peter Paul Rubens to Rembrandt created elaborate systems of production, as have modern artists like Jeff Koons and Andy Warhol, who famously declared his art to be a factory-produced commodity.

And legal experts said that claims of inadequate credit by an underling generally have faced a tough road because courts require proof that the person who filed for a work’s copyright, Mr. Chihuly in this case, intended to share credit of authorship.

Credit

Ben Hider/The New York Botanical Garden

“I think no one would have even assumed that Chihuly did all his own work, first of all, because there’s too much of it,” said Christine Steiner, a lawyer in Los Angeles who represents galleries, artists and museums, but does no work for Chihuly.

In both law and art value assessment, she said, works that go out the door of an artist’s studio, however they are produced, are generally deemed to be a product of that artist’s vision. Because of that, she said she sees little effect on Chihuly art-market values no matter what happens in the case.

But the Chihuly case also opens up what many artists say is an uncomfortable and complicated debate about age, infirmity and the foibles of human nature where one person is in control, egos are large, and vast fortunes are being made.

“Any artist is going to suck up all the energy in the room,” said Toots Zynsky, a glass artist who studied with Mr. Chihuly in the 1970s and remains friends with him. “So the more you admire someone, the less you should work for them.”

Ms. Zynsky trained at the Rhode Island School of Design in the early ’70s, as did Mr. Beers, the architect, when Mr. Chihuly was teaching in the school’s famous glass program. She said she decided early in her career that assistants should never become long-term employees — three years and out became her rule — because she feared she might stunt their style and growth or take too much from them in creating her own art.

Another artist who has known Mr. Chihuly for many years said he believes Mr. Chihuly is still making “Chihuly art,” even if others are constructing and finishing it.

“As long as Dale can put it down on paper, right to the very end I think he’ll be able to keep going,” said Benjamin Moore, a glass artist in Seattle. But Mr. Moore said he has also been saddened by the attacks on his friend, and the decline in Mr. Chihuly’s vitality over the last decade.

“He was such a whirlwind of energy and excitement and enthusiasm, he was like a magnet, drawing the most talented young people around him just to be in his presence to learn,” Mr. Moore said. “But he’s a shell of the man that he was — it breaks my heart.”

In the lawsuit, where pretrial motions are underway, Mr. Moi said the level of Mr. Chihuly’s disabilities were never disclosed to art buyers or the public and that Chihuly Studio often intimated that Mr. Chihuly’s paintings were entirely by his own hand. Other legal cases in recent years involving Mr. Chihuly and his former employees — him suing them or vice versa — were settled out of court, but those disputes could be dredged up again in depositions or testimony as the case goes forward.

“For years Leslie Chihuly and Chihuly Studio have undertaken efforts to hide Dale’s struggles with mental health and his inability to work on a daily basis, not to protect him, but to ensure that the cash cow known as ‘Chihuly’ continued to moo,” Mr. Moi’s suit says.

Mr. Chihuly, who said he now rarely paints for more than an hour or two at a time, perhaps three days a week, was working on a recent morning, surrounded by four assistants. One handed him a brush, then held the paint container at his elbow as he stood over a horizontal glass sheet, partly painted already with specially formulated enamel, composed of ground glass suspended in liquid.

“Do you want one over the other, or do you want it side by side?” Mr. Chihuly turned to ask an assistant, Jodie Nelson, referring to the blotched paint dobs that he was about to apply.

Ms. Nelson’s response was immediate: “I want what you want.”

Mr. Chihuly then proceeded to paint, in sweeping, fast brush strokes as a Bob Dylan song played in the background. The goal, he said, was to approximate, but not fully duplicate, two other glass painted images that would then be put together, fired and then lit for display, creating an illusion of three dimensions, called “Glass on Glass.” The design is still new — only displayed for the first time recently at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas. During a pause, he gestured to one of the glass layer paintings hanging on back wall. “I rejected that one this morning,” he said. “I don’t like the way it looks.”

There’s no question Mr. Chihuly has become an institution and created a bridge between decorative and fine arts that some art scholars have compared to Louis Comfort Tiffany. Chihuly Studio creates some 30 site-specific pieces a year, ranging in price from $200,000 to millions of dollars, and has done commissions for collectors like Bill Gates and Bill Clinton. Mr. Chihuly’s show at the New York Botanical Garden, through Oct. 29, has drawn more than 484,000 visitors since April, making it one of most attended exhibitions in the garden’s history.

At Chihuly Studio on a recent afternoon, workers were assembling a huge glass chandelier for a university, tinkering with a sculpture scheduled for installation in Union Square Park in New York, and painting flower images on glass in three big warehouselike buildings in Seattle’s Ballard neighborhood.

Seattle became an art-glass capital largely because of Mr. Chihuly, through the Pilchuck Glass School, a nonprofit academy north of the city that he helped found in 1971, and the two museums built around his work or glass art in general. Chihuly Garden and Glass, which opened in Seattle in 2012 next to the Space Needle, is the city’s top-ranked tourist attraction on TripAdvisor, and has become a cash cow of its own. Admission costs $29, and the gift shops sells everything from Chihuly umbrellas ($36), to blankets ($500), to numbered prints of Chihuly paintings (about $3,000).

“Second on my list of things to see, after the Space Needle,” said Alison Yeardley, a fourth-grade teacher from Boston, who was spending three days of her vacation in Seattle and had just left the Chihuly Garden and Museum on a recent morning.

Mr. Chihuly said that in looking back over the long arc of his career, he can pretty much pinpoint where his mental state was, in the cycles of up or down. In the mid ’90s, for example, he remembers working for weeks with little sleep on a project to build and hang chandeliers over the canals of Venice. But then a couple of months later, working at Waterford Crystal in Ireland, he said, the cycle turned. “I was depressed, but yet I had my team with me and I could continue to work,” he said.

“I like my work when I’m up,” he added. “Van Gogh, you know, he worked when he was depressed as well as when he was up, and I’ve never been able to figure it out.”

Mr. Beers, the former student, said he looks back on those early mornings in the glass shop in Rhode Island partly as a response to the practical realities of working in front of a furnace, seizing time before the heat of the day, but also for the quiet sense of calm that seemed part of the experience for Mr. Chihuly and his students.

“It was a more peaceful sort of Zen time, that early in the morning,” Mr. Beers said. “Or maybe he just couldn’t sleep, and it was time to get to work.”

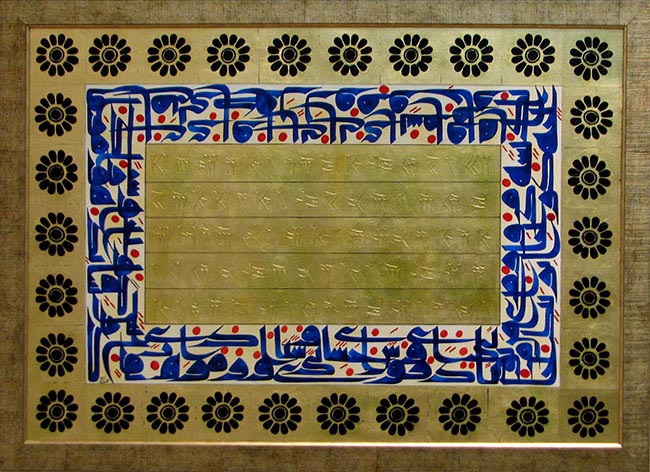

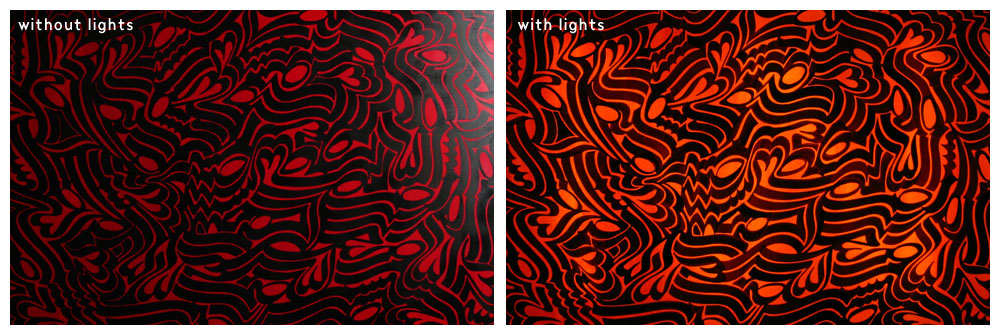

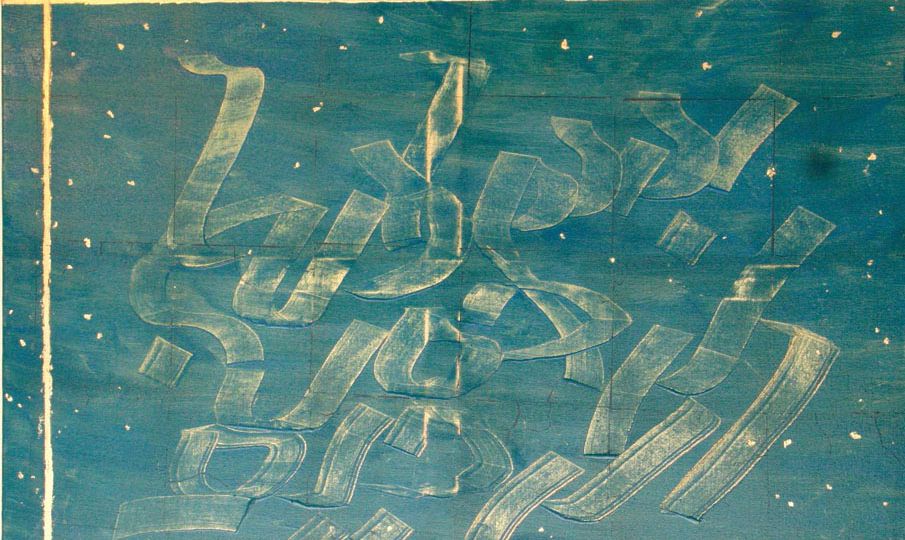

3d calligraphy | Calligraphy | Modern Calligraphy | 09121958036 | ebrahimolfat.com