So you don’t miss the contemporary angle, the Met commissioned Tanabe Chikuunsai IV, a fourth-generation bamboo artist born in 1973, to create an installation piece that looms over the entrance to the show. “The Gate,” as it is called, is two thick entwined coils that twist upward from the floor and spread out along the ceiling. Their scale is imposing; they evoke twin baby cyclones or, less violent, the bifurcated trunk of an ancient banyan tree, but their open-weave, light-colored Tiger bamboo is semitransparent and sort of weightless. These forms have an animated-cartoon energy and snap; they cavort almost wickedly. Throughout the exhibition you will see basketry abstracted, deconstructed and all but exploded in the hands of successive generations of artists. In 1975 Tanabe Yota (1944-2008), a younger brother of Tanabe Chikuunsai III, created “Earth Dedicated to Children,” a low-lying mountain (or volcano) form that looks like a miniature earthwork, or maybe a model for James Turrell’s “Roden Crater.”

Credit

Jake Naughton for The New York Times

In a show like this, baskets can start to look like one of the world’s most complete, resonant art mediums. The characteristic Japanese reverence for nature is reflected in titles referring — usually with justification — to waves, blossoming flowers or moonlight, but it also comes across directly and physically. Basketry’s processes do not extensively transform bamboo, as is the case with so much else — ceramics or lacquer, say, or for that matter oil painting. The central technique is weaving. There will usually be some cutting or slicing, often into exquisitely thin strands, and maybe some soaking beforehand; along the way rattan might be used for reinforcement and, toward the finish, lacquer may be applied. But that’s about it. We stay remarkably close to the original natural material, which submits to spectacular skill and structural concepts without losing its identity.

Credit

Jake Naughton for The New York Times

The linear structure of bamboo basketry maintains a remarkable clarity. It can effortlessly combine aspects of sculpture, textiles and also architecture, and when the weaves are open suggest fully dimensional drawings in space. But bamboo basketry also accommodates what might be called crazy-quilt departures from the grid, as in the crisscrossing darn-stitch weave of Nagakura Ken’ichi’s round “Sister Moon Flower Basket” of 2004 — an intensely covetable, fittingly concave and seemingly inward-looking piece that the Abbeys perhaps understandably are keeping. And the physical variety of bamboo accommodates many sensibilities and degrees of refinement, from intricate forms and patterns that look like computer planning was required, to the relative crudeness of the exuberant “Dancing Frog Flower Basket,” with its flamboyantly twisted handle and aggressive weave, made by Hayakawa Shokosai III (1864-1922) in 1918.

As with many of the crafts that the Japanese have cultivated into art, great aid came from China, specifically in the refined baskets that began arriving in the 13th century for use in Esoteric Buddhist rituals and soon became part of traditional Japanese tea ceremonies. Chinese forms continue into the present, like the elevated offering tray from 2012 by Fujinuma Noboru, born in 1945 and now designated a Living National Treasure in Japan. “Peerless Fruit or Offering Tray” very much lives up to its name.

But until the end of the 19th century, bamboo basketry lagged behind lacquer, ceramics and calligraphy in its art status. While all of the Abbey bamboo artists are known, the names of those represented in the Moore bequest are not, except Hayakawa Shokosai I (1815-1897), thought to be the first Japanese bamboo master to sign his works. The Moore bequest’s Shokosai I is a large and regal Chinese-style flower basket that has the silhouette of a Ming dynasty stoneware storage jar (similar to the one sitting beside it). The Abbeys have enhanced this masterwork with two more of his pieces: a wonderful anomaly in the form of a perfectly bowled bowler hat in bamboo and rattan and a boxy yet gently swelling lidded basket for transporting tea ceremony utensils.

Credit

Jake Naughton for The New York Times

Since Shokosai I’s time, basketry has tended to be dynastic, usually along the male line, since the craft traditionally involves cutting your own bamboo. The two women represented in the show — Kajiwara Aya, born in 1941, and Isohi Setsuko, 1964 — may be a sign of change, but for the most part bamboo art is handed down from father to son or from a master to an apprentice. Tanabe Chikuunsai IV is preceded by Tanabe Chikuunsai III, II and I, with examples of the clan’s impressive efforts lined up in front of “Misty Bamboo on a Distant Mountain,” an atmospheric ink painting by the Chinese artist Zheng Xie from 1753. It is one of several stirring, sometimes carefully matched pairings of baskets and two-dimensional works. My favorite involves a hanging scroll by the great Yosa Buson. Near it, you will find a one-man dynasty named Iizuka Rokansai (1890-1958), represented by seven basketry works whose variations in color, purpose, form and fineness make an especially breathtaking moment in a show splendidly full of them.

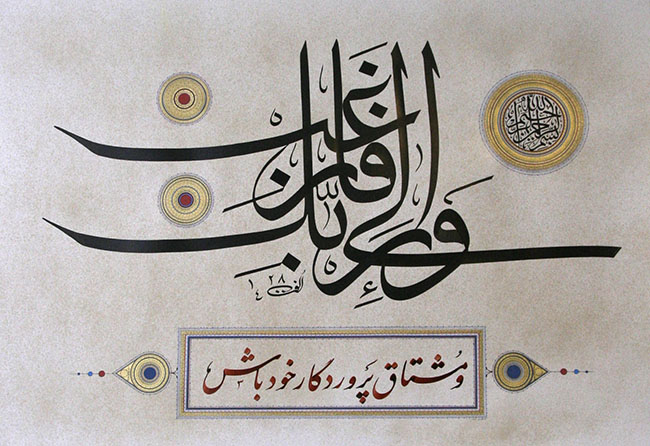

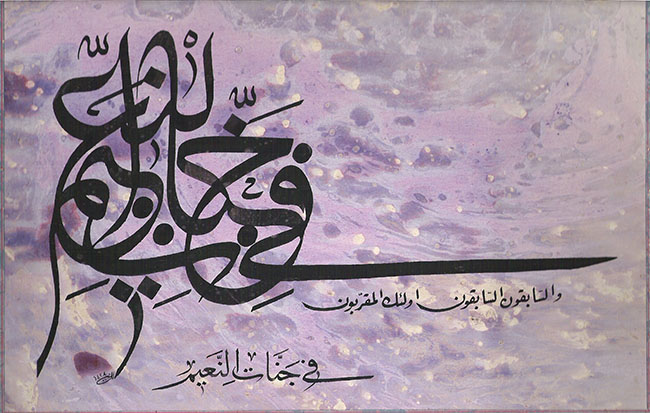

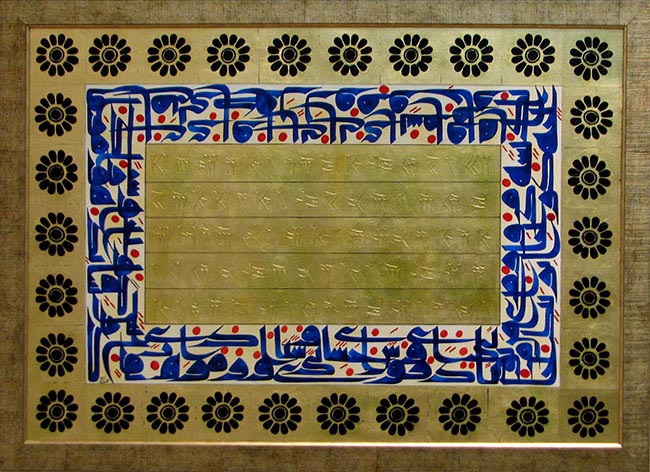

Ebrahim olfat | Calligraphy | Modern Calligraphy | 09121958036 | ebrahimolfat.com