After the fall of the Third Reich, Eichmann was briefly in American custody. He escaped, lived on a chicken farm for two years, then fled again, eventually making his way to Argentina. In time he obtained a job with Mercedes-Benz — his employee ID card is here, with his assumed name, Ricardo Klement, beneath his chillingly recognizable photograph in thick spectacles. He might have lived out his days there, but in 1956 a German-Jewish émigré grew concerned about a boy his daughter was dating, and determined that the boy’s father was a wanted man. He alerted a German state prosecutor, who soon made contact with Israeli intelligence.

The bulk of “Operation Finale” is devoted to Eichmann’s abduction from Argentina, masterminded by the Mossad and encouraged by David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s founding prime minister. Investigators compared Nazi-era portraits to surveillance photographs and confirmed, by the shape of his ears, that Klement was indeed Eichmann. A team of more than two dozen Israeli agents was dispatched, and on May 11, 1960, the team snatched him off Garibaldi Street, bundling him into a car with bogus license plates. We see the keys and cigarette holder he had when he was kidnapped. Here is Eichmann’s false Israeli passport, used to board a delayed El Al flight, and the taped-over goggles he wore all the way to Tel Aviv. There is also newly filmed testimony from Rafi Eitan, an agent in the operation, though the overproduced videos in this show are bombastic and superficial, more appropriate to the History channel than to a rigorous exhibition.

Ben-Gurion’s announcement that Eichmann was in Israeli custody and would be prosecuted under Israeli law shocked the world. The trial was held nine months later, in a converted theater in Jerusalem, and is recreated in the final gallery here via three video projections arrayed around the unnerving, immediately recognizable defendant’s box. The image of Eichmann, impassive, untroubled, his lips pursed, is projected behind the glass booth, while to either side are the judges, the prosecutors, the spectators, and more than a dozen witnesses testifying, one by one, to what they had seen and suffered in the death camps.

Eichmann was convicted, sentenced to death and hanged in 1962: the only civil execution in Israel’s history. (That could change if Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, has his way; last week he called for a reintroduction of the death penalty after the killings of several Israeli settlers in the West Bank.) A number of Israeli intellectuals, including the philosopher Martin Buber, pleaded for a commutation of the death sentence, on the grounds that “we are granting a victory for the enemy over us, and we do not want this victory.” But most Israelis were relieved, and the Eichmann trial began a new chapter for Holocaust survivors, who now spoke more openly of what they had endured after two decades of public silence.

Credit

John Halpern

The trial was transformative, but whether it was entirely just is not a question raised by this exhibition, which prefers the relics of James Bond-like spycraft to moral and legal dilemmas. Hannah Arendt, who covered the trial for The New Yorker, is briefly name-checked in a final video, but there is little engagement with the enduring philosophical questions she raised on the meaning of justice, on individual versus state guilt, and on the shades of difference between “crimes against humanity” and “crimes against the Jewish people.”

The legality of Eichmann’s abduction and juridical legacy of the trial are also shortchanged. Eichmann, after all, was kidnapped from a sovereign nation without warning, and American newspaper editorials, not to mention the American Jewish Committee, sharply criticized Israel’s actions. (Argentina lodged a complaint with the United Nations Security Council, which was later withdrawn.)

And while Eichmann’s crimes predated the foundation of the State of Israel, the court set an important precedent by affirming that it had universal jurisdiction over crimes as grave as genocide. It also placed, in a way the Nuremberg trials did not, the voices of victims at the heart of the proceedings. Arendt considered those individual voices extraneous to the question of Eichmann’s guilt, but victims’ testimonies have since become a central plank in the practice of international justice.

These philosophical dilemmas and legal repercussions don’t much trouble “Operation Finale,” whose overly pat narrative may reflect its genesis within an Israeli government institution. Yet standing in front of the dock, that upright glass coffin familiar from a thousand newsreels, is a humbling experience. Not only does it contract the barbarism of the Holocaust into a single, indelible form; it also looks forward, and serves as a quiet commendation of the troubled institution built to prosecute the Eichmanns of our own age. That is the International Criminal Court in The Hague, which the United States — and Israel too — refuse to join.

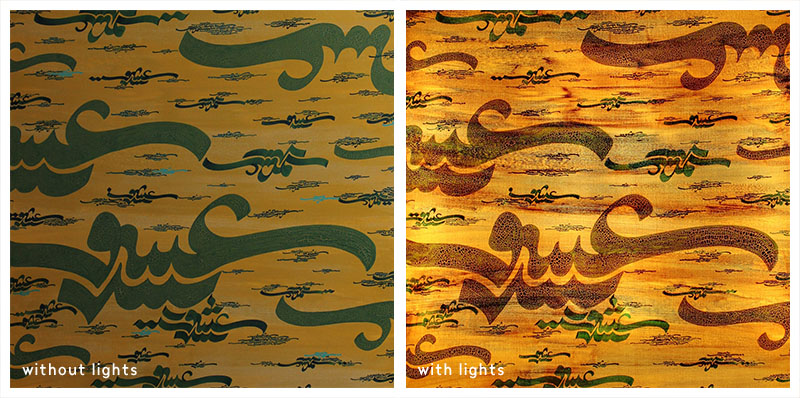

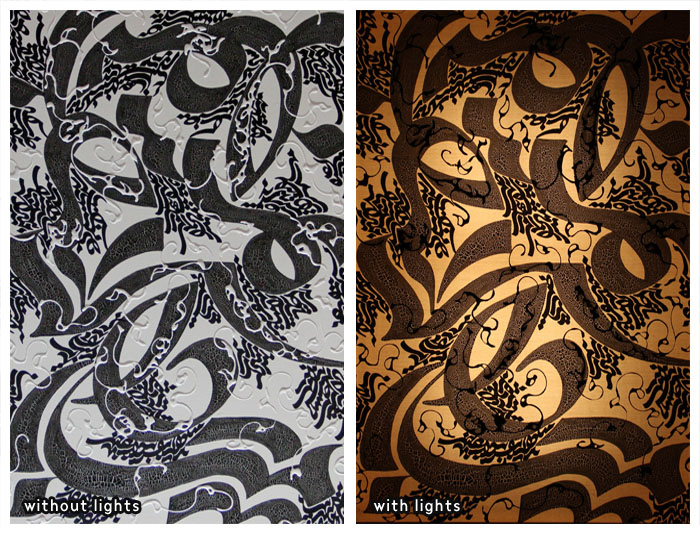

Ebrahim olfat | Calligraphy | Modern Calligraphy | 09121958036 | ebrahimolfat.com