Rauschenberg, like Ms. Halprin and Ms. Kawakubo, was never afraid of bad taste. You might say that these three, collectively, have a philosophy that holds when something seems right, it’s probably wrong. So do the opposite.

Just as Rauschenberg didn’t pay attention to artistic categories — he was a painter, photographer, collagist, sculptor and even at times a dancer and choreographer — Ms. Halprin turned against the practice of inventing and maintaining a codified dance technique. Instead, she focused on improvisational methods, dancing in the natural world and using dance as a healing tool.

For “Radical Bodies,” three curators — Ninotchka D. Bennahum, Wendy Perron and Bruce Robertson — teamed up to show how postmodern dance, which developed in the 1960s in New York, didn’t happen by magic on the East Coast. Its roots were planted by Ms. Halprin in California and allowed to grow with the help of two of her students, Ms. Forti and Ms. Rainer.

“Radical Bodies” feels less like a conventional exhibition than a story illustrated with objects. Photographs bring the past to life and videos dance on the walls in this presentation of ideas born out of a fateful meeting: In 1960, Ms. Forti and Ms. Rainer attended a workshop with Ms. Halprin, held on her now-famous open-air dance deck in Marin County, California.

The setting is crucial. For Ms. Halprin, nature is a partner. As Ms. Perron noted in a joint interview with Ms. Bennahum, “On her deck, the trees are moving.”

For Ms. Bennahum, “It feels like a very intimate theater, except for that rather than walls, you have trees — and sky.”

Soon after that 1960 workshop, Ms. Forti and Ms. Rainer found themselves in New York. Ms. Forti began to show her “Dance Constructions,” works based on ordinary movement and objects like plywood boards; and Ms. Rainer went on to become a founder of the experimental dance collective Judson Dance Theater.

It’s easy to see how the dance artists of the 1960s were radical. But Ms. Kawakubo and Rauschenberg are part of the conversation, too. You try things out. You fail. You start over. And sometimes, an ordinary body breaks the rules: It becomes radical.

Credit

Susan Landor

Anna Halprin: Getting Naked Together

As violence ravaged cities across America in the 1960s, Ms. Halprin — reacting to the 1968 assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the race riots in South Central Los Angeles — held weekly workshop sessions in Watts, commuting from the Bay Area. In an interview in her book, “Moving Toward Live: Five Decades of Transformational Dance,” Ms. Halprin says, “I wanted to do a production with a community instead of for a community.”

She also began to conduct a similar workshop with a troupe of white dancers in San Francisco. She united the two groups to create “Ceremony of Us,” a healing dance performed in 1969. Though they were working toward a performance, the workshops were just as important as the end result. Ms. Halprin’s aim was to integrate black and white bodies — physically, psychologically and sociologically.

While no footage exists of the performance, the film “Right On/Ceremony of Us” depicts rehearsals. “It’s very erotic, they get naked, they lick each other, they kiss each other, they hold each other,” Ms. Bennahum said. “It’s very sensual.” And, as this image of tightly knit bodies shows, endlessly arresting.

Credit

Barbara Moore/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY, via Paula Cooper Gallery, New York and 2016 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation; Photograph by Peter Moore

Robert Rauschenberg Takes Flight

Who would Rauschenberg have been if he didn’t know dancers? Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor, Trisha Brown, those luminaries of modern and postmodern dance, were part of his inner circle. It’s no coincidence that his visual art was full of dimension and breadth. He understood dance — and how to design for it. His entire career was a radical body of work.

One showstopper at MoMA’s exhibition “Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends” is Ms. Brown’s “Glacial Decoy” (1979) — the installation was created with MoMA’s curatorial and exhibition design teams in collaboration with Charles Atlas — in which Rauschenberg’s revolving black-and-white photographs are grandly displayed on a back wall as the dance is projected on top. It’s as gossamer-delicate as the gowns, also by Rauschenberg, that the dancers wear.

“Among Friends” unravels Rauschenberg’s effervescent imagination and enthusiasms that, for a time, extended to choreography. In “Pelican,” he and Alex Hay performed on roller skates, part of a choreographic investigation in which performers interacted with objects.

They wore cargo chutes extended on rods and attached to backpacks. Mr. Hay, in a museum recording, admits that it was somewhat scary to perform. “The problem was when we had to circle around Carolyn Brown” — another dancer — “and not engage these two cargo chutes,” he says. “I guess they were about eight feet wide, extended.” Here, the body is made radical by its expanded form, which gives it a blend of oddball humor and danger. Mercifully, no one fell.

As a part of a special presentation on Sept. 6, the museum will present dances associated with Rauschenberg — by Brown, Cunningham and Mr. Taylor — in the Sculpture Garden.

Credit

Andrea Mohin/The New York Times

Rei Kawakubo: Changing Equilibrium

When Ms. Kawakubo’s clothing, no matter how sculptural, is displayed on a mannequin, it’s still inert. In that sense, the Metropolitan Museum’s show “Rei Kawakubo/Comme des Garçons: Art of the In-Between” resembles one of Ms. Kawakubo’s stores; it even ends with something akin to a pop-up shop, where visitors can buy tote bags and a version of her 1982 hole sweater. Ms. Kawakubo slyly turns the museum exhibition into business as usual.

Ms. Kawakubo refuses to call herself an artist. Whether she is or isn’t, one thing seems true: The clothes aren’t art on their own. The wearer gives them life. It’s exciting to realize that even Comme des Garçons is merely material without a partner: a willing, confident and radical body.

For her breakthrough “Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body” (1997), Ms. Kawakubo created a collection that transformed the body with clothing enhanced by bulbous bumps placed in places meant to do anything but flatter. The padding distorted the lines of the hips, backs, shoulders and chests. She told Vogue at the time: “It’s our job to question convention. If we don’t take risks, then who will?”

Credit

Agaton Strom for The New York Times

Using the same approach as for that collection, Ms. Kawakubo designed the costumes — as well as the white setting — for Merce Cunningham’s dance “Scenario,” which changed his performers’ physicality as efficiently as would a risky step. Their proportions altered, the dancers’ equilibrium was thrown off; what happened to their coordination, their spacing?

Ms. Kawakubo gave them new bodies, and Cunningham, with typical wit, reacted with his singular “Scenario.” At the Met, the dance is screened on monitors on a platform where pieces from the collection are displayed. And this matters: We need to see the clothes in action.

When it comes to the artistry of Ms. Kawakubo, you have to wear her (and I do) to know her. It isn’t like putting on a costume; it’s about finding your true self. And that’s radical.

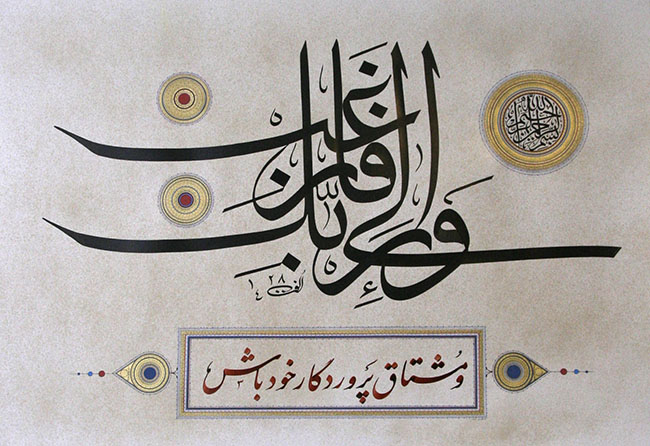

Ebrahim olfat | Calligraphy | Modern Calligraphy | 09121958036 | ebrahimolfat.com